“I have known Charley Macdonald since the earliest days of golf in this country and for many years we have been rival course architects, and I really mean rivals for in many instances we widely disagreed. Our matter of designing courses never reconciled. I stubbornly insisted on following natural suggestions of terrain, creating new types of holes as suggested by Nature, even when resorting to artificial methods of construction. Charley, equally convinced that working strictly to models was best, turned out some famous courses. Throughout the years we argued good-naturedly about it.”

If you were to take A.W. Tillinghast’s word for it, the Golden Age of Golf Course Architecture was broken into two camps: those using templates, and those going without. There’s a kernel of truth to this…and plenty untrue as well. Tillie, for all his hay about the “natural suggestions of terrain,” frequently turned to templates. Tillinghast went as far as developing his own portfolio of templates. There are four, and this series will shed some light on these “lesser templates,” typically ignored in today’s conversations on the subject of designed holes.

The first is the most frequented of Tillie’s templates, but rarely receives recognition as being just that…a “template.” The reason may be the huge variety present across this template’s history; Macdonald and Raynor always incorporated some degree of ingenuity into their own templates, but Tillinghast’s variance in this concept may fool some into not recognizing it as a template at all. And MacRaynor’s use of a similar (yet distinct!) concept doesn’t help Tillie’s cause.

And so today we look at the Tiny Tim.

THE BIG IDEA

“Tiny Tim should be a little Tartar, impressive and inspiring as it stands forth. It must be one of the show holes of the course, beautiful as a siren, yet quite as guilefully dangerous.”

This description, noted by Tillinghast in Gleanings From The Wayside, doesn’t suggest much to the 21st Century reader aside from noting a strong aesthetic appeal. His use of the term “Tartar” is meaningful: The region of “Tartary” alluded to a huge swath of Central Asia, and encompassed races as varied as the Mongols and the Turks. Basically, to a white person of Tillie’s era, a “Tartar” was a tough customer. His phrase “little Tartar,” then, is a short hole with big teeth, surrounded by hazards for those who fail to land.

If this sounds like Macdonald’s “Short” template, you’re not wrong. Although both tend to be of the same length, Macdonald and Raynor are more consistent in their creation of large, wide greens, while Tillinghast tended toward greens of smaller ilk. The general idea was the same; precision within a short distance. But for Macdonald and Raynor, an inaccurate shot often resulted in a challenging putt, while for Tillinghast it often meant a severe recovery shot (not to say you couldn’t find putting trouble on a Tiny Tim. More on that soon).

It should be noted that Tillinghast—perhaps because of his supposed non-template affiliations—did not assign the term “Tiny Tim” to this style of hole. Aside from the original, we can find no indication that he referred to any of his holes of similar specifications by that title. He emphasized a range in Par 3 lengths across his career. It’s interesting to note how many of his shortest options came packaged with an artillery of hazard, which we would argue marks the existence of a conceptual template in Tillie’s mind (if not a named one, per se).

THE ORIGINAL

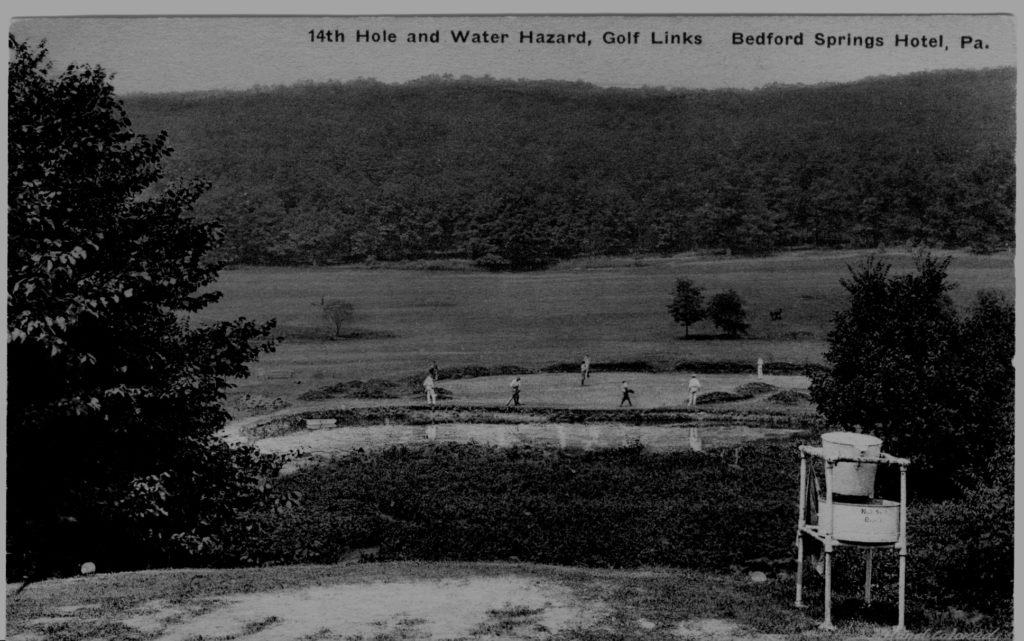

It’s clear from his writings that Tillinghast was confident in the Tiny Tim concept early on; the passage quoted above was created during his work at Bedford Springs, his second project, where the hole still bears the “Tiny Tim” moniker. This instance, more than any other in the Tiny Tim collection, throws the kitchen sink at players in terms of hazards. At the fore, the player must overcome nerves and cross both Shobers Run and an additional pond short of the green. Surrounding the circular green, five bunkers ring the clock from about 9:00 to 5:00. At the front left is a series of man-made humps, nicknamed the “Alps,” which partially pay tribute to the course’s original Spencer Oldham design. Although not an immense green, it’s hardly small in relation to the rest of Bedford’s offerings.

The biggest question to ask is why Tillinghast didn’t emphasize large greens on this or future Tiny Tims? I’ve got a few theories (and maybe others have expressed similar thoughts). On one hand, Tillie was not shy about taking concepts to their logical extremes. The “Great Hazard” is a more threatening version of the “Long” template, so why not do the same thing with Macdonald’s “Short” (which had debuted at the National Golf Links four years earlier)? Shrink the green and make a more demanding tee shot. It’s no secret that Tillinghast paid attention to Macdonald’s work, but Tiny Tim is no copycat. Quite the opposite. In my own experience, I write a templates education series for another publisher. One of my first steps when creating an outline is to check out The Fried Egg’s template series—not to learn, but to ensure I’m not blatantly ripping them off. I go out of my ways to find different examples, even stretching to apply the strategy of that template to modern holes. In short, I may not be breaking new ground, but I’m also not plagiarizing. Tillinghast may have experienced something similar when conceptualizing Tiny Tim. After all, the theory behind “Short” is remarkably simple. Horace Hutchinson had the same in mind when he created No. 4 at Royal West Norfolk (we know this, because the Scot advised Macdonald directly on the Short concept). Tillie may have simply wanted a way to place his brand on the same idea.

And he made a lot of tweaks in its later application.

TWEAKS

Tillinghast was not shy about working this template into his designs. What perplexes those searching for Tiny Tims is that they’ve rarely remained consistent with their intended length…another victim of the distance wars. Fortunately, there are some instances where the original “tiny” intent exists. The San Francisco Golf Club hosts just such a hole. Standing at a current distance of 134 yards, the green at No. 13, the green is minuscule, much longer than it is wide (but still not that long). Surrounding it are four colossal bunkers with much more floorspace than the green. Although the wind may be less a factor, it resembles a more weaponized “Postage Stamp,” the infamous No. 8 at Royal Troon. Tillinghast never specifically referenced this hole, but it often serves as a better comparison point to Tiny Tim than Macdonald’s Short. His 112-yard Par 3 at Philadelphia Cricket Club has maintained its micro-status, albeit with a much larger green.

The good news for Macdonald—perhaps because his courses are trod far less by professional golfers—is his Shorts have remained short. Tillinghast’s Tiny Tims have more generally seen some growth. Baltusrol’s Lower course demonstrates such an instance with its first Par 3. The No. 4 hole follows a very similar approach to the original Tiny Tim, fronted by a pond all the way up, and surrounded by bunkers elsewhere. The “Tillinghast” tees, playing from a separate teebox, come out to 186 yards. Step down to the “Baltusrol” tees with the rest of us mortals, and you’ll be looking at 143. The green here is significantly larger than the aforementioned examples, so—as with a Short—a green-in-regulation is not a guaranteed anything.

Even with Tillie’s smaller Tiny Tim greens, green-in-regulation does not mean much. One of my personal favorites is the example at Quaker Ridge. The club’s site compares the green to the famous Redan, which is not inaccurate in the recommended angle of approach. It differs from traditional Redans in both length (it currently tips at 165, perhaps 30 yards shorter than the average Redan) and size of green. This green is also armed to the teeth. A standard Redan is no pushover, but the four cavernous bunkers seen here are next level. Tillinghast has been known to flex the Redan, and here he seemingly hybridized it with his own personal branding.

We are all familiar by now with Tillinghast’s boldness, and its role inspiring monoliths such as the Great Hazard template. The bones behind Tiny Tim allowed Tillinghast to touch at another exotic idea…the island green. Pete Dye made the concept famous, and Herbert Strong created a very generous island at Ponte Vedra, but Tillinghast was arguably the first. His “Moat Hole” at Galen Hall played too much like a Par 3.5 to be considered a “Tiny Tim” (at 190 yards), but it is truly surrounded by water on all sides. A more conservative example came at Somerset Hills No. 12 “Despair.” The entire front and left of the green is flanked with a lake, the right will native grass, and a bunker sits at the back (chipping downward to a green that slants toward the lake is no joke). Not an island, but certainly a savage Tartar.

MODERN TAKES

There’s an immediate difficulty in finding “modern” takes on the Tiny Tim, and it comes from a distance perspective. More modern architects are usually aiming at a more modern audience, which means more distance, even for such “short” holes. For example, the famous No. 5 at Teeth of The Dog is very much like the aforementioned “Despair,” but at 176 yards, we would suggest it pushes the necessary yardage just a tad too far (everything is relative, of course, and on Dye’s scorecard, it is indeed quite short). The relative simplicity of the green is there, however. At Streamsong Red’s No. 8, the distance is fine, but the S-bend of the green is too much, however.

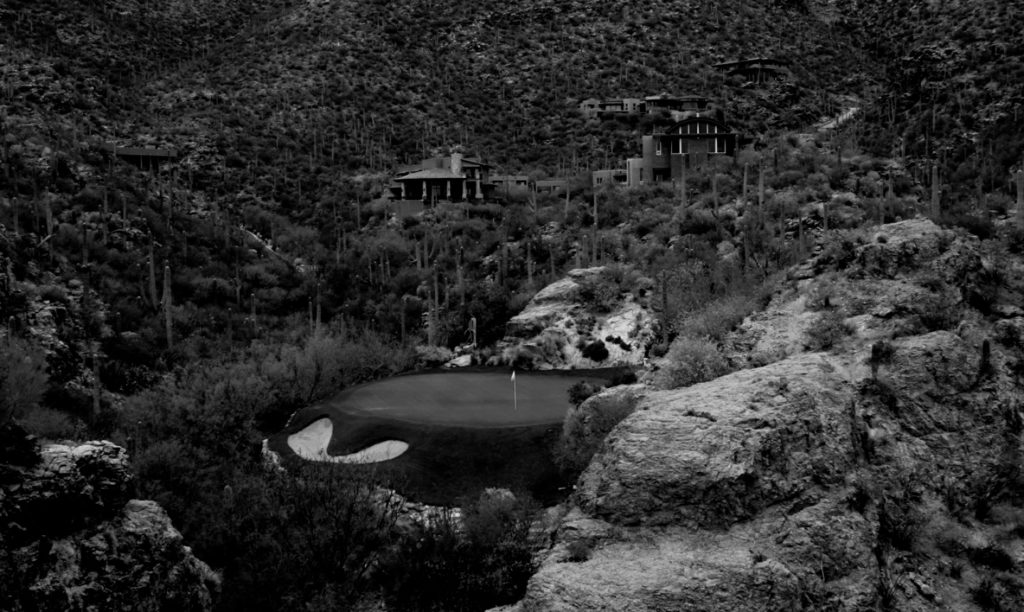

There are still examples to be had. Consider the simplicity in the life-or-death equation that is No. 3 at Tom Fazio’s Mountain Course at the Ventana Resort. A mere 107 yards from the tips, the only “safe” miss is into the bunker built into the steep front-left of this green, nestled among the titular mountain. No. 11 at Giant’s Ridge also passes muster; a pond wraps around the front and right, and a chicken-foot bunker sits at the left. Hitting over this green leaves a truly Tillinghast scenario, as pitching up and onto this green (which runs the other way) is a hazard unto itself. It is unlikely that either Fazio or Jeff Brauer had “Tiny Tim” in mind; as a template, this is a touch obscure. The concept, however, is near universal.

NOT GREAT HAZARDS

There are rare instances, of course, where Tillinghast left Par 3s at championship-caliber courses both short and without a minefield of hazard surrounding them. Winged Foot East, for example, has two short holes that peak at 146 and 148yards, respectively, and neither has much Tillie terror surrounding them (the similarity in distances itself is peculiar for ol’ A.W.).

More challenging are Par 3s that Tillinghast did surround with such terror, but don’t necessarily meet the prescribed standards. The most infamous example is No. 17 at Bethpage Black, a course Tillinghast had intended to be a hellion from the get-go (Joseph Burbeck is acknowledged for fostering this attitude, but he’s not getting course credit from this publication). Accordingly, this peanut green among brazil-nut bunkers was more than 170 yards at its inception. Not quite madness for the era, but arguably more intense than the standards established by carries at previous Tiny Tims.

Tillinghast’s templates, especially now that we’ve gotten past the Great Hazard, are hardly a science, so chime in. Next time we’ll get back to one of his longer numbers, the Double Dogleg.